Evaluation and interpretation of data prior to remediation strategy

Published: May 26th, 2008

Revised: July 21st, 2014

Overview

This mold reference provides the most current and comprehensive discussion on the basic practice of identifying mold damage, the evaluation of the samples that are collected, and the process of remediation. Its twenty chapters cover the underlying principles and background of evaluation and control, building evaluation, data interpretation, remediation and control, plus appendices containing advanced perspectives in mold prevention and control, and images of exterior and interior building mold. This extensive management of indoor mold discussion was written by expert industrial hygiene practitioners, academics and government officials and scientists scrutinized by external peer review. Innovative methods and approaches for each assessed situation are provided.

Click here to read the chapter >

Sampling duration and recovery of culturable fungi

Published: May 3rd, 2008

Revised: July 21st, 2014

Abstract

The influence of sampling duration on recovery of culturable fungi was compared using the Andersen N6 and the Reuter Centrifugal Sampler (RCS). Samplers were operated side-by-side, collecting 15 samples each of incrementally increasing duration (1–15 min). From 270 samples collected, 26 fungal genera were recovered. Species of Alternaria, Aspergillus, Cladosporium, Epicoccum, Penicillium and Ulocladium were most frequent. Data adjusted to CFU/m³ were fitted to a Poisson regression model with a logarithmic link function and evaluated for the impact of sampling time on qualitative and quantitative recovery of fungi, both as individual taxa and in aggregate according to xerotolerance. Significant differences between the two samplers were observed for xerotolerant and normotolerant moulds, as well as Aspergillus spp. and Cladosporium spp. With the exception of Cladosporium spp., overall recoveries were higher with the RCS. When the Andersen N6 was used, the recovered levels of Cladosporium spp. and unidentified yeasts were reduced significantly at sampling times over 6 min. Similarly, when the RCS was used, recovery of Aspergillus spp., Penicillium spp., Ulocladium spp., unidentified yeasts, and low water activity fungi declined significantly at sampling times over 6 min.

View the full PDF article >

The Distilleries’ Shadow: A summary of knowledge about Baudoinia, the warehouse staining fungus

Published: May 1st, 2008

Revised: August 18th, 2009

During the 1870s, the pharmacist Antonin Baudoin called attention to a black, soot-like growth on buildings near spirit maturation warehouses in the famous town of Cognac, France. The nature of the dark “cryptogamic plant” growing on walls, roof tiles, tree trunks and fences was debated by the experts: was it a fungus or a blue-green alga? In 1881, it was definitively classified as a fungus and named Torula compniacensis (meaning ‘the torula from Cognac,’ popularly known as “la torule” in Cognac itself. The old genus name Torula, from 1794, means “little rounded thing.”). Then, remarkably, the fungus was forgotten by science for 80 years. It was briefly studied by Scandinavian and French researchers in the 1960s, then forgotten again. Finally, in the late 1990s, when the public became aware of health problems associated with the growth of black moulds in water-damaged buildings, the widespread occurrence of soot-like fungal growth around distilleries attracted attention and aroused suspicion.

During the 1870s, the pharmacist Antonin Baudoin called attention to a black, soot-like growth on buildings near spirit maturation warehouses in the famous town of Cognac, France. The nature of the dark “cryptogamic plant” growing on walls, roof tiles, tree trunks and fences was debated by the experts: was it a fungus or a blue-green alga? In 1881, it was definitively classified as a fungus and named Torula compniacensis (meaning ‘the torula from Cognac,’ popularly known as “la torule” in Cognac itself. The old genus name Torula, from 1794, means “little rounded thing.”). Then, remarkably, the fungus was forgotten by science for 80 years. It was briefly studied by Scandinavian and French researchers in the 1960s, then forgotten again. Finally, in the late 1990s, when the public became aware of health problems associated with the growth of black moulds in water-damaged buildings, the widespread occurrence of soot-like fungal growth around distilleries attracted attention and aroused suspicion.

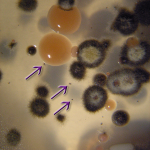

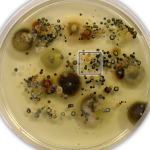

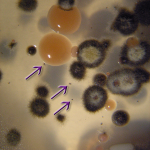

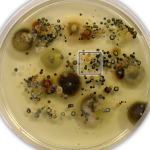

The nature of the fungus, however, baffled modern experts: ordinary culturing techniques as well as the most modern genetic sampling techniques were confounded by a dusting of ubiquitous, contaminating “weed” fungi that accumulated on top of the primary black growth. Eventually, the problem was solved by using very patient culturing with an unusual twist: since the fungus seemed to grow only where ethanol vapours were present in the air, ethanol was also added to the growth medium at low concentration. Even though the fungus was extremely slow growing, it then grew well enough to be sorted out from the overlying “weeds” and brought into pure culture.

The nature of the fungus, however, baffled modern experts: ordinary culturing techniques as well as the most modern genetic sampling techniques were confounded by a dusting of ubiquitous, contaminating “weed” fungi that accumulated on top of the primary black growth. Eventually, the problem was solved by using very patient culturing with an unusual twist: since the fungus seemed to grow only where ethanol vapours were present in the air, ethanol was also added to the growth medium at low concentration. Even though the fungus was extremely slow growing, it then grew well enough to be sorted out from the overlying “weeds” and brought into pure culture.

The fungus grows as dark spots, streaks or clumps that under the microscope can be seen to be composed of short chains of dark, rounded cells. The cells have a rough wall; that and the fact that the chains break into fragments tend to make la torule look like microscopic dead debris. By comparison, the more elegantly formed cells of co-occurring “weed” fungi like Cladosporium are more likely to attract attention. To determine the biological relationship of the very nondescript torule, modern gene sequencing techniques were necessary. Remarkably, the organism was found to be most closely related to a fungal family, the Friedmanniomycetaceae, best known for growing inside porous rocks in Antarctica. Since it was completely unrelated to any fungus correctly called Torula, it had to be given a new scientific genus name. The name “Baudoinia” was chosen, after the pharmacist who first brought the fungus to scientific attention. The most typical cultures thus became the species Baudoinia compniacensis, “Baudoin’s [fungus] from Cognac.” Other, still-undescribed species of Baudoinia occur in numerous locales worldwide.

The fungus grows as dark spots, streaks or clumps that under the microscope can be seen to be composed of short chains of dark, rounded cells. The cells have a rough wall; that and the fact that the chains break into fragments tend to make la torule look like microscopic dead debris. By comparison, the more elegantly formed cells of co-occurring “weed” fungi like Cladosporium are more likely to attract attention. To determine the biological relationship of the very nondescript torule, modern gene sequencing techniques were necessary. Remarkably, the organism was found to be most closely related to a fungal family, the Friedmanniomycetaceae, best known for growing inside porous rocks in Antarctica. Since it was completely unrelated to any fungus correctly called Torula, it had to be given a new scientific genus name. The name “Baudoinia” was chosen, after the pharmacist who first brought the fungus to scientific attention. The most typical cultures thus became the species Baudoinia compniacensis, “Baudoin’s [fungus] from Cognac.” Other, still-undescribed species of Baudoinia occur in numerous locales worldwide.

Laboratory studies have shown that B. compniacensis can use ethanol as a source of energy for growth, although it prefers to live on other, more nutritive materials. This preference is confirmed by field observations near maturation warehouses in which airborne levels of alcohol alone are typically far too low to account for the accumulated fungal mass. Baudoinia also shows a remarkable tolerance of high temperatures, not unexpectedly for a fungus growing on exposed surfaces. The temperature tolerance of the fungus is enhanced if it is exposed to ethanol first. Protein studies have confirmed that ethanol exposure stimulates the formation of protective “heat shock proteins” that confer heat resistance.

The rationale for researching Baudoinia is based on finding ways to deter its growth and, at the same time, ascertaining whether or not it has any allergenic or other health significance. Common antifungal remedies like copper and zinc salts improve short-term resistance on a range of materials, but have not enabled long-term growth deterrence. It is hoped that further studies on the organism’s physiology and genetics will provide more sophisticated remedies. Given that the actual amount of ethanol in the air in sites where the organism grows appear insufficient to support growth, further studies are also needed to determine how exactly the organism maintains its existence, and what role ethanol really plays in facilitating its growth.

L’ombre des distilleries: Un sommaire des connaissances sur Baudoinia, le champignon recouvrant les murs des chais

Published: May 1st, 2008

Revised: August 18th, 2009

C’est au cours des années 1870 que le pharmacien Antonin Baudoin signala la présence d’un organisme noirâtre ressemblant à de la suie qui se développait sur les murs des bâtiments avoisinant les chais de vieillissement de la célèbre ville de Cognac, en France. La nature de cette obscure «plante cryptogamique» croissant sur les murs, les tuiles, les troncs d’arbre et les clôtures fut débattue par les experts: s’agissait-il d’un champignon ou d’une cyanobactérie? En 1881, l’organisme fut définitivement classé parmi les champignons et nommé Torula compniacensis, c’est-à-dire «le torule de Cognac», communément désigné sous le nom de «le torule» à Cognac. L’ancienne désignation du genre Torula, datant de 1794, signifie «petite chose arrondie». Puis, chose étonnante, ce champignon fut oublié par les scientifiques pendant 80 ans. Il fut brièvement étudié par des chercheurs scandinaves et français dans les années 1960 pour sombrer de nouveau dans l’oubli. Il fallut attendre la fin des années 1990, lorsque les problèmes de santé associés aux moisissures noires dans les bâtiments endommagés par l’eau furent portés à la connaissance du public, pour que la présence généralisée de cette croissance fongique ressemblant à de la suie à proximité des chais attire l’attention et éveille les soupçons.

C’est au cours des années 1870 que le pharmacien Antonin Baudoin signala la présence d’un organisme noirâtre ressemblant à de la suie qui se développait sur les murs des bâtiments avoisinant les chais de vieillissement de la célèbre ville de Cognac, en France. La nature de cette obscure «plante cryptogamique» croissant sur les murs, les tuiles, les troncs d’arbre et les clôtures fut débattue par les experts: s’agissait-il d’un champignon ou d’une cyanobactérie? En 1881, l’organisme fut définitivement classé parmi les champignons et nommé Torula compniacensis, c’est-à-dire «le torule de Cognac», communément désigné sous le nom de «le torule» à Cognac. L’ancienne désignation du genre Torula, datant de 1794, signifie «petite chose arrondie». Puis, chose étonnante, ce champignon fut oublié par les scientifiques pendant 80 ans. Il fut brièvement étudié par des chercheurs scandinaves et français dans les années 1960 pour sombrer de nouveau dans l’oubli. Il fallut attendre la fin des années 1990, lorsque les problèmes de santé associés aux moisissures noires dans les bâtiments endommagés par l’eau furent portés à la connaissance du public, pour que la présence généralisée de cette croissance fongique ressemblant à de la suie à proximité des chais attire l’attention et éveille les soupçons.

La nature de ce champignon, toutefois, laissait les experts modernes perplexes: l’application des techniques de mise en culture courantes et d’échantillonnage génétique les plus modernes s’avéraient difficiles du fait de la présence continuelle de contaminants qui s’accumulaient sous forme de « poussière » sur la croissance noire originale. Le problème fut finalement résolu à l’aide d’une mise en culture méticuleuse recourant à une technique inhabituelle : puisque le champignon semblait croître uniquement dans les milieux où l’air contenait des vapeurs d’éthanol, une faible concentration d’éthanol fut ajoutée au milieu de culture. Bien que sa croissance ait été extrêmement lente, l’organisme a poussé suffisamment bien pour pouvoir être isolé des contaminants et placé en culture pure.

La nature de ce champignon, toutefois, laissait les experts modernes perplexes: l’application des techniques de mise en culture courantes et d’échantillonnage génétique les plus modernes s’avéraient difficiles du fait de la présence continuelle de contaminants qui s’accumulaient sous forme de « poussière » sur la croissance noire originale. Le problème fut finalement résolu à l’aide d’une mise en culture méticuleuse recourant à une technique inhabituelle : puisque le champignon semblait croître uniquement dans les milieux où l’air contenait des vapeurs d’éthanol, une faible concentration d’éthanol fut ajoutée au milieu de culture. Bien que sa croissance ait été extrêmement lente, l’organisme a poussé suffisamment bien pour pouvoir être isolé des contaminants et placé en culture pure.

Le champignon se présente sous forme de taches, de traînées ou de plaques de couleur sombre qui, examinées au microscope, apparaissent composées de courtes chaînes de cellules foncées et arrondies. Les cellules ont une membrane chagrinée; c’est cette caractéristique et le fait que les chaînes se brisent en fragments qui font que le torule ressemble à des débris morts microscopiques. En comparaison, les cellules de forme plus élégante des contaminants qui lui sont associés comme Cladosporium sont plus susceptibles d’attirer l’attention. Il a fallu recourir aux techniques modernes de séquençage génétique pour déterminer l’affinité biologique du torule, totalement dépourvu de traits distinctifs. On a pu constater que l’organisme était étroitement lié à la famille des Friedmanniomycetaceae, surtout connue par sa présence dans les roches poreuses de l’Antarctique. Puisqu’il n’avait aucun lien avec le champignon appelé correctement Torula, il fallut créer un nouveau genre scientifique pour le désigner. Le nom « Baudoinia » fut choisi, en l’honneur du pharmacien qui fut le premier à le porter à l’attention des scientifiques. Les cultures les plus caractéristiques devinrent ainsi l’espèce Baudoinia compniacensis, «[le champignon de] Baudoin de Cognac.» Il existe d’autres espèces encore non décrites de Baudoinia dans de nombreux milieux de par le monde.

Le champignon se présente sous forme de taches, de traînées ou de plaques de couleur sombre qui, examinées au microscope, apparaissent composées de courtes chaînes de cellules foncées et arrondies. Les cellules ont une membrane chagrinée; c’est cette caractéristique et le fait que les chaînes se brisent en fragments qui font que le torule ressemble à des débris morts microscopiques. En comparaison, les cellules de forme plus élégante des contaminants qui lui sont associés comme Cladosporium sont plus susceptibles d’attirer l’attention. Il a fallu recourir aux techniques modernes de séquençage génétique pour déterminer l’affinité biologique du torule, totalement dépourvu de traits distinctifs. On a pu constater que l’organisme était étroitement lié à la famille des Friedmanniomycetaceae, surtout connue par sa présence dans les roches poreuses de l’Antarctique. Puisqu’il n’avait aucun lien avec le champignon appelé correctement Torula, il fallut créer un nouveau genre scientifique pour le désigner. Le nom « Baudoinia » fut choisi, en l’honneur du pharmacien qui fut le premier à le porter à l’attention des scientifiques. Les cultures les plus caractéristiques devinrent ainsi l’espèce Baudoinia compniacensis, «[le champignon de] Baudoin de Cognac.» Il existe d’autres espèces encore non décrites de Baudoinia dans de nombreux milieux de par le monde.

Des études de laboratoire ont montré que B. compniacensis a la capacité d’utiliser l’éthanol comme source d’énergie pour pousser, bien qu’il préfère vivre sur d’autres substrats plus nutritifs. Cette préférence a été confirmée par des observations sur le terrain menées près des chais où les concentrations d’alcool de l’air seules sont typiquement bien trop faibles pour être à l’origine de la masse fongique accumulée. Baudoinia semble également présenter une tolérance remarquable aux températures élevées, ce qui ne saurait surprendre d’un champignon poussant sur des surfaces exposées. Cette tolérance est accrue lorsque le champignon a été exposé au préalable à l’éthanol. Des études sur les protéines ont permis de confirmer que l’exposition à l’éthanol stimule la formation de «protéines de choc thermique» protectrices qui confèrent une résistance à la chaleur.

Les chercheurs étudient Baudoinia en vue de trouver des façons de freiner sa croissance et, par la même occasion, de déterminer s’il a des effets allergènes ou nocifs sur la santé. Les agents antifongiques comme les sels de cuivre et de zinc améliorent la résistance à court terme de toute une gamme de matériaux, mais n’ont pas eu d’effet inhibiteur à long terme. Il est à espérer que les caractéristiques physiologiques et génétiques de l’organisme nous permettront de produire des agents inhibiteurs plus sophistiqués. Vu que la quantité actuelle d’éthanol dans l’air ambiant où vit cet organisme semble insuffisante pour soutenir sa croissance, il faudra mener d’autres études pour connaître la façon dont l’organisme se maintient en vie et le rôle que joue l’éthanol dans sa croissance.

Ethanol physiology in the warehouse staining fungus, Baudoinia compniacensis

Published: May 1st, 2008

Revised: July 21st, 2014

Abstract

The fungus Baudoinia compniacensis colonizes the exterior surfaces of a range of materials, such as buildings, outdoor furnishings, fences, signs, and vegetation, in regions subject to periodic exposure to low levels of ethanol vapour, such as those in the vicinity of distillery aging warehouses and commercial bakeries. Here we investigated the basis of ethanol metabolism in Baudoinia and investigate the role of ethanol in cell germination and growth. Germination of mycelia of Baudoinia was enhanced by up to roughly 1 d exposure to low ethanol concentrations, optimally 10 ppm when delivered in vapour form and 5 mM in liquid form. However, growth was strongly inhibited following exposure to higher ethanol concentrations for shorter durations (e.g., 1.7 M for 6 h). We found that ethanol was catabolized into central metabolism via alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ACDH). Isocitrate dehydrogenases (IDHs) were active in cells grown on glucose, but these enzymes were not expressed when ethanol was provided as a sole or companion carbon source. The glyoxylate cycle enzymes isocitrate lyase (ICL) and malate synthase (MS) activities observed in cells grown on acetate were comparable to those reported for other microorganisms. By replenishing tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates, it is likely that the functionality of the glyoxylate cycle is important in the establishment of luxuriant growth of Baudoinia compniacensis on ethanol-exposed, nutrient- deprived, exposed surfaces. In other fungi, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, ADH II catalyses the conversion of ethanol to acetaldehyde, which then can be metabolized via the TCA cycle. ADH II is known to be strongly repressed in the presence of glucose.